Putting terrorist threats into context

Ahead of the Security & Counter Terror Expo, Richard English, Professor of Politics at Queen’s University Belfast, seeks to question whether terrorism is working and work out what terrorism does and does not tend to achieve

If we want to limit the incidence of terrorism in the future, then we need to ask two central questions. Firstly, how can societies and governments make terrorism a less appealing and common mode of political struggle? Secondly, how can we limit the success of terrorists once they have - tragically and regrettably - carried out an attack or series of attacks. The first question tries to minimise the number of atrocities that take place; the second seeks to limit the damage that is done once violence has actually occurred. The two questions are inter-related, but let’s them both in turn.

The evidence is overwhelming that most terrorists engage in what they do because they sincerely believe that their violence is the only way of bringing about necessary and desirable political change. This has been true from the anarchists of the late nineteenth century, to the IRA of 1919-21, to the Jewish terrorists who sought to establish the state of Israel in the mid-twentieth century, to waves of Palestinian organisation which have sought to advance Palestinian nationalism, to the Provisional IRA, to al-Qaida, to ISIS and beyond.

For anyone committed to a precious political cause – whether it be ideologically nationalistic, religious or left- or right-wing – one key question to ask is the question of how best to bring about the change that they passionately seek.

And here there has been a tendency for people on all sides to exaggerate what terrorism has actually achieved. At a strategic level, people more commonly think of those rare cases when terrorism achieves its central goals (the Jewish terrorism which helped to bring about the creation of Israel, for example, or the Hezbollah terrorism of the 1980s which prompted US and French forces to withdraw from the Lebanon) than they do of the far more numerous instances in which terrorist groups have failed to achieve such strategic victory. All of us – whether politicians, police officers, military employees, business people, voters, journalists, teachers, or whoever – need to be clear about this central aspect of the history of terrorism: that terrorism rarely achieves its central goals.

What it far more commonly achieves lies instead in the realm of secondary goals. So Hamas have been and remain unable to destroy the state of Israel and replace it with an Islamic Palestinian state covering the full territory of Mandate Palestine. What they have done is achieve considerable revenge against Israeli and Jewish targets – most of them defenceless at the point of the attack. But if terrorism is far likelier to achieve revenge against the defenceless than it is to secure political victory – and if people recognise this widely and honestly – then it becomes a less appealing method to deploy.

For many terrorist groups have found that their callous violence against the defenceless has, over time, lost them political support. One of the reasons for the Provisional IRA moving away from their violence was that many Catholics in Northern Ireland would not support their politics while the bombs were going off; once the IRA shifted its methods, many more people would vote for their political party, Sinn Fein, than would have done so had the IRA carried on killing people. Similarly, one of the reasons for al-Qaida not becoming pervasively popular among most of the world’s Muslims was the unpopularity of their violence – especially their violence against civilians.

From the IRA to al-Qaida and beyond to other major groups such as the Basque separatists in ETA, the historical reality is that terrorist methods did not yield strategic victory; what they yielded was far more often a form of violence which many within their supposed constituency found repugnant and increasingly repellent the longer that it went on.

Any journalist or politician who wants to contribute to a safer society should focus on these truths in the wake of a terrorist atrocity, rather than concentrating on denouncing the evil quality of the perpetrator. For the arguments that I’ve just set out are far more likely to undermine the central thinking pushing people towards terrorism, namely their mistaken view that it is the best or only way of achieving political change.

Limiting the effects

But terrorism as a method will continue to be with us, even if such arguments persuade some people not to pursue it. How can we limit the effects of the violence once it has happened, once an attack has occurred or a campaign has begun?

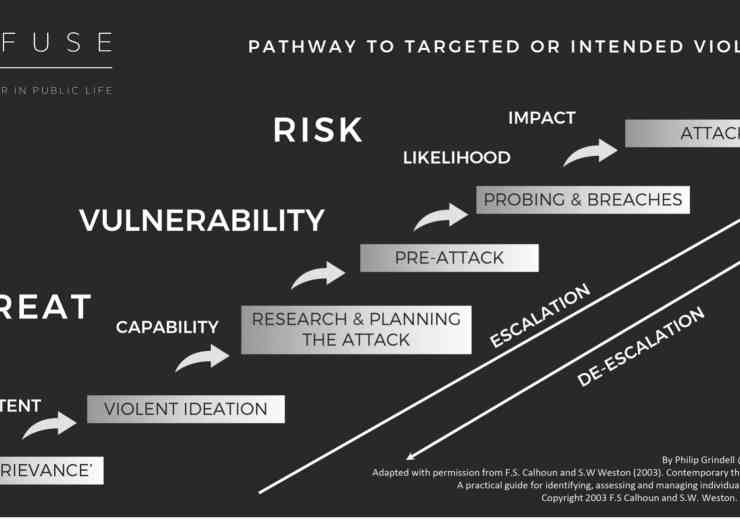

A key aspect here is to avoid exaggerating the scale of the threat. One of the things that terrorists have often succeeded in doing is undermining the societies that they attack, and this depends often on the over-reaction of the society in question. In reality, terrorism is an extraordinarily low-level threat in terms of the likelihood of anyone in the UK or America, for example, being killed by its violence.

This does not lessen the awfulness of terrorist atrocity for its victims, but if we want there to be fewer victims in the future then we need not to exaggerate the threat to the extent that we counter-productively over-react to it and actually make it worse. In the wake of 9/11, there was an exaggeration of the degree to which al-Qaida represented a threat to the West, and this legitimated an overly militaristic response which in turn led to terrorist incidents rising rather than falling. Had there been a more proportionate response and a less exaggerated reading of the post-9/11 al-Qaida threat, then the chaos in Iraq would not have been created and the emergence of ISIS would have been far less likely.

So suggestions that groups like ISIS represent an existential threat to the UK, or to Western democracy, are so far from the truth that they merely give gifts to terrorists, making terrorism seem more powerful than it is. And they make us more likely to over-react in ways that will make terrorist recruitment and activity easier rather than more difficult.

Much of this relates to the media. Of course journalists should report and discuss terrorist attacks, and should be able to do so freely. But in doing so they should stress the real nature and scale of the threat, which is limited. In the United States, people are far less likely to be killed by a terrorist than they are to be killed by colliding with a deer in a traffic accident, by being struck by lightning, by drowning in the bath, or by dying in a household accident. Keeping the terrorist threat in proportion will allow us to limit the damage that terrorists do to our society when they attack; it will also make it less likely that we over-react and thereby do their recruiting for them through overly aggressive foreign policy or through unnecessarily polarising domestic legislation.

Honest politicians and realistic aims

We can also minimise the damage done by terrorists if we avoid setting ourselves unrealistic targets and goals. To talk of getting rid of terrorism, of removing radical Islamic terrorism from the world, is to set the bar so high for ourselves that all terrorist groups have to do to be able to claim victory is to carry on their violent existence. A more sensible way of proceeding is to state – calmly and patiently – that some political causes generate terrorism; that the threat will endure but that it can be contained in ways that allow us to live our resilient life as democratic societies; and that on the basis of the historical record, victory for terrorists will elude them in terms of their central, strategic ambitions.

Some politicians may find this an unappealing set of principles, but many of their citizens and voters want the political class essentially to protect them and to tell them the truth. And the truth is that terrorism is very unlikely to bring about strategic victory for the terrorists; the truth is that it will produce horrific suffering for its victims, most of whom tend to be defenceless when they are attacked; the truth is that it represents a low-level threat to the vast majority of people; and the truth is that Western democracies have repeatedly shown that they can endure the conflict with terrorists in impressively resilient fashion.

If we want to protect people from terrorism, then reflecting in these ways on what terrorism does and does not tend to achieve allows for a powerful defence against such a painful and unjustified mode of political struggle.

Richard English is Professor of Politics at Queen’s University Belfast, and the author of Does Terrorism Work? A History (Oxford University Press, 2016).