A look at terrorist financing

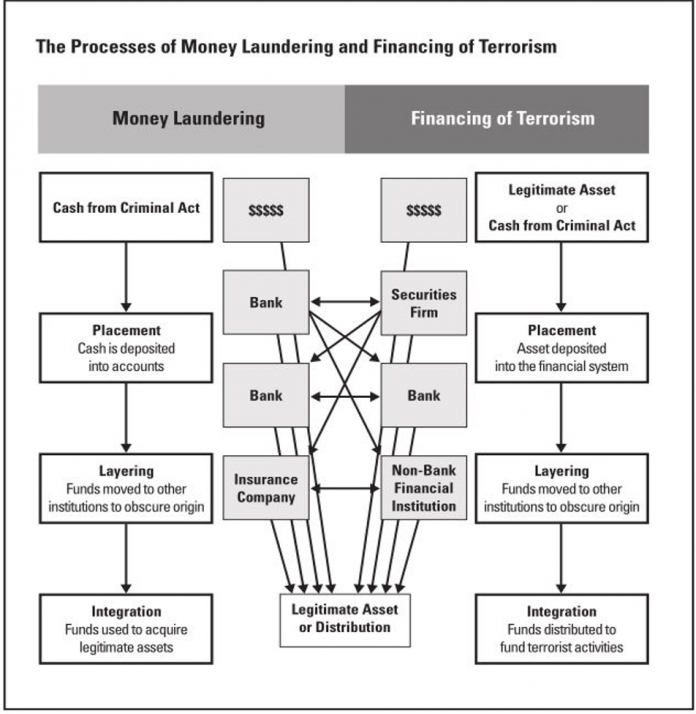

Hear from Debbie Rafferty, counter terrorism consultant and PhD student, Abertay University (Dundee), speak at International Security Expo 2022, 28th September, 10:30 – 12:30 on Mitigating Security in the North Sea. There is one inexorable circumstance which relates to terrorism, the prerequisite for financing and the proviso of a continuous stream of substantial funds (Yousif, 2009). From a structural viewpoint, terrorist organisations ought to be contrasted to major corporations. Therefore, in this context, it is useful to deliberate a terrorist organisation as a business and evaluate the success, or otherwise, of the approaches adopted to secure funding (investment). Further, against this backdrop, terrorist groups require a paradigm to plan how revenue can be generated and sustained (Byrne, 2012). Consequently, terrorist organisations must continuously generate funds to cover expenses in order to sustain their operations. From an organisational perspective, terrorist organizations should be likened to major corporations and cash inflow is the lifeblood (Bush, 2001) of any terrorist or establishment, to survive and develop (Schneider, 2017). In this context, how an organisation makes revenue and how it incurs cost, is central to the organisation’s efficiency and effectiveness and is influenced by many factors. Consequently, these units must continuously generate funds and distribute sufficient money in order to sustain operations (Jamwal, 2007). Vittori, (2011, p.15) describes these as “Life’s necessities”. Therefore, a terrorist organisation requires extensive capital, and a balanced revenue of funds from the point of origin to the point of distribution. Deprived of cash, terrorists are confronted with risk that could result in the demise of the group. To begin, terrorists utilise diverse strategies to acquire funds and there are innumerable often untraceable variations (Neumann, 2018). To complicate matters, there are clear links between terrorist groups and organised crime, the connection between these entities is primarily driven by financial profit and gain (Stanojoska, 2011). Much like a corporation, a terrorist organisation must establish reliable funding streams that adequately meet and ideally surpass fixed and variable costs. Therefore, in general, terrorist organisations must expedite the acquisition of aforesaid funds at a relentless pace and central to this are sources of reliable funds. Hence, terrorists use extensive methods to move money within and between organisations, including the financial sector and the transfer of cash by carriers, and goods through commerce (Lormel, 2018). Charitable trusts and payment systems have been used to conceal the terrorist movement of funds. The flexibility and resourcefulness exhibited by terrorist organisations means global finance and processes are at risk to illegal activities (Financial Action Task Force, 2018). Some terrorist organisations have started using organised crime conduits, therefore the links between transnational (Sedgwick, 2007), organised crime (TOC) and foreign terrorist organisations (FTO), are tangible, as are the escalating alliances between them. The need for finance of the terrorist goals means terrorist organisations continue to involve criminal business. Theorists like Makarenko, have referred to this phenomenon as “the crime-terror nexus.” (Makarenko, 2000 p. 259). Further, the imperative to raise finance has given birth to many hybrid funding strategies, on a local, national or global scale. Capital and the terrorist mission and support can be expensive and the variety of money-making schemes have become essential elements of the terrorist fund-raising repertoire (Abuza, 2003). Each component of the terrorist funding sequence (raise, move, store and spend) avails a means to strive to understand the complicated and elaborate process of terrorist financing. In an ideal world, it should be uncomplicated to trace funds from origin to the end user. Unfortunately, the myriad of financial sources, methods of movement and access points make identifying and tracing terrorist financing extremely difficult (Tavares, 2004; Indridason, 2008; Gross et.al. 2016) and laborious, given the seemingly infinite funding variations (Von Lampe, 2014). In general, it is problematic to ascertain trends in money laundering and terrorist financing (FATF-GAFI, 2005). Moreover, corrupt money is netted through various criminal activities, like drug, weapon and human trafficking. Baker (2005) estimates the illegal money to range between US$ 1.0 and 1.6 trillion a year. Further, the IMF calculates that the total sum of corrupt finance through the fiscal system is between 500 billion USD and 1,500 billion USD a year, which amounts to 3 per cent and 5 per cent of the aggregate world product, however this is an estimate. A broad sweep reveals that organisational revenue streams include, however are not confined to, revenue from business activity; locally raised revenue; and revenue from conventional terrorist financing. In general, funds are either generated through internal sources, taxation of people, enterprises and transport routes; income from kidnap and ransom; and profits from trade. Also, external funding is given by donors supportive to the cause (zakat) (as cited in Benda-Beckmann, Franz von, 2007), often affluent followers, Gulf state countries called the Golden Chain (1989) or affiliates of the movement. Each terrorist organisation accesses finance using unique methods, often there are similarities, however significant differences are present. In reviewing the aforesaid, it is sensible to understand the philosophy which motivates these violent organisations, this provides a lens to examine the innumerable sources of funding in respect of terrorist organisations. Hezbollah, as an example, receives money from Emdad committee for Islamic Charity, Hezbollah Central Press Office, Al Jarha Association, and Jihad Al Binaa Developmental Association, while a second exemplar, Boko Haram accepts funds from foreign Islamic charities (UK and Saudi Arabia) (Agbiboa, 2013). Although it is difficult to identify the main characteristics in Boko Haram’s funding and the group has a decidedly differentiated financing strategy, often opportunistic and impromptu micro fundraising operations (Appendix 3) support many of its operations by lawless activity, including bank theft, abductions (Chibok girls, 2014) assassinations for hire, smuggling, livestock theft and extortion (Home Office, 2019). There appear to be interconnections between transnational organised crime and transnational terrorism, ‘legitimate’ businesses, levying taxes, trafficking (drugs, goods and humans), flora and fauna poaching, forced donations, counterfeit, and misappropriation of humanitarian subsidises and commercial profits (Rose, 2018). A significant difference between the groups can be found when they have the ability to “live off the land” (Zenn and Cristiani, 2016). These “shell states” (Napoleoni, 2005, p. 65) are exploited allowing a capitalizing on the impoverished and fragile areas like the north of Nigeria in order to extract money from civilians. Money laundering is a source of funding employed by many terrorist organisations. Non-conventional money transferring systems like Hawala system/transactions allow funds to be transferred without actual currency movement (Razavy, 2005; Perkel, 2004), defined as ‘underground banking’ (Bunt, 2007). Levitt and Jacobson (2008) illuminate bankrolling as a product of glocalisation, globalisation and scientific developments, which have permitted terrorist groups to solicit, deposit, reassign, and disseminate funds for operations. Trilateral drug trafficking in Latin America, Africa and Europe accounts for over 2 billion US dollars annually. The channels include, mass cash running operations and Lebanese exchange firms. Originating in South Asia access to the system is world-wide, this makes it popular with groups like Hezbollah, who launder narcotics proceeds via the Halawi Exchange Co. (Halawi) (FAFT Report, 2013). Actions including re-routing benevolent donations, the manipulation of non-governmental establishments (NGOs), participation in illegitimate activities and smuggled goods bring about large dividends. Finally, terrorist groups operate in a complicated global arena and data discloses the intricate and international trade and finance routes, illegal and legal. Astute sponsors are adept at using a variety of processes to perform transactions, regardless of location, so as to hide the source of the funds received. This highlights the reliance of these groups on not only criminal proceeds, but also revenue from proxy sources and funding campaigns. Finally, the fundraising apparatus of both organisations is intricate and obscure, as are the elusive militants themselves. Sources: Abuza, Z. 2003, Militant Islam in Southeast Asia: crucible of terror, Lynne Rienner Publishers. Agbiboa, D. 2013, "The ongoing campaign of terror in Nigeria: Boko Haram versus the state", Stability: International Journal of Security and Development, vol. 2, no. 3. Ajakaye, R. 2009, "Credible Elections Lies in Attitudinal Change Not INEC Chirman, Ezeani", Daily Independent. Ammani, A.A. 2010, Boko Haram uprising: Not seeing the Woods for the Trees. Azani, E. 2013, "The hybrid terrorist organization: Hezbollah as a case study", Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, vol. 36, no. 11, pp. 899-916. Baker, P. 2010, "Representations of Islam in British broadsheet and tabloid newspapers 1999–2005", Journal of Language and Politics, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 310-338. Baker, R.W. 2005, Capitalism's Achilles heel: Dirty money and how to renew the free-market system, John Wiley & Sons. Bush, G.W. 2001, We will starve the terrorists. Byman, D. 2005, Deadly connections: States that sponsor terrorism, Cambridge University Press. Cristiani, D. & Zenn, J. 2016, "AQIM’s resurgence: Responding to Islamic state", Terrorism Monitor–The Jamestown Foundation, vol. 14, no. 5. DeVore, M.R. 2012, "Exploring the iran-hezbollah relationship: A case study of how state sponsorship affects terrorist group decision-making", Perspectives on Terrorism, vol. 6, no. 4-5. Flanigan, S.T. & Abdel‐Samad, M. 2009, "Hezbollah's social jihad: Nonprofits as resistance organizations", Middle East Policy, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 122-137. Gupta, D.K. 2005, "Exploring roots of terrorism" in Root causes of terrorism Routledge, pp. 34-50. Harik, J. 1994, The public and social services of the Lebanese militias, Centre for Lebanese studies Oxford. Hoffman, B. 1998, "[BOOK REVIEW] Inside terrorism", Survival, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 204-205. Indridason, I.H. 2008, "Does terrorism influence domestic politics? Coalition formation and terrorist incidents", Journal of Peace Research, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 241-259. International Crisis Group 2014, "Curbing Violence in Nigeria (II): The Boko Haram Insurgency", Crisis Group Africa. Iyekekpolo, W.O. 2016, "Boko Haram: understanding the context", Third World Quarterly, vol. 37, no. 12, pp. 2211-2228. Jamwal, N. 2002, "Terrorist financing and support structures in Jammu and Kashmir", Strategic Analysis, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 140-150. Koh, J. 2006, Suppressing terrorist financing and money laundering, Springer, Berlin. Makarenko, T. 2000, "Crime and terrorism in Central Asia", Janes Intelligence Review, vol. 12, no. 7, pp. 16-17. Napoleoni, L. 2004, Terror incorporated: tracing the dollars behind the terror networks, Seven Stories Press. Norton, A.R. 2014, Hezbollah: A Short History-Updated Edition, Princeton University Press. Phillips, B.J. 2017, "Deadlier in the US? On lone wolves, terrorist groups, and attack lethality", Terrorism and political violence, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 533-549. Robbins, J.S. 2002, "The jihad online", National review online, vol. 30. Rose, G. 2018, "Terrorism Financing in Foreign Conflict Zones", Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 11-16. Rudner, M. 2010, "Hizbullah terrorism finance: fund-raising and money-laundering", Studies in conflict and terrorism, vol. 33, no. 8, pp. 700-715. Schneider, F. 2017, "Macroeconomics: The financial flows of islamic terrorism" in Global Financial Crime Routledge, pp. 107-134. Stanojoska, A. 2011, "The Connection between Terrorism and Organized Crime: Narcoterrorism and other Hybrids". Tavares, J. 2004, "The open society assesses its enemies: shocks, disasters and terrorist attacks", Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 1039-1070. Tofangsaz, H. 2012, "A new approach to the criminalization of terrorist financing and its compatibility with Sharia law", Journal of Money Laundering Control, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 396-406. Vittori, J. 2011, Terrorist financing and resourcing, Springer. Von Lampe, K. 2014, "Recent publications on organized crime", Trends in Organized Crime, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 342-344. Woodford, I. & Smith, M.L.R. 2018, "The Political Economy of the Provos: Inside the Finances of the Provisional IRA—A Revision", Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 213-240. Yousif, B. 2009, "Jeanne Giraldo and Harold Trinkunas, eds. Terrorism Financing and State Responses: A Comparative Perspective. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007. xi 384 pages, endnotes, index. Paper US $24.95 ISBN 978-0-8047-5566-3.", Review of Middle East Studies, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 86-88.