The role of symbolism in terrorist attacks

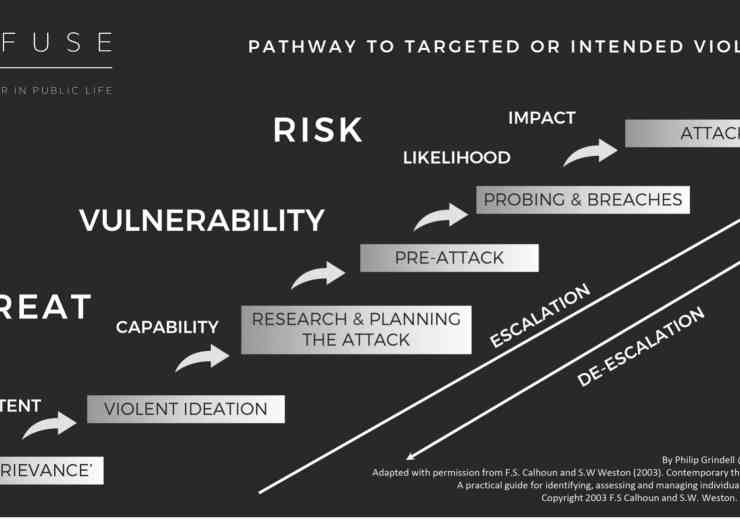

Imagine for one minute that you are a terrorist. Perhaps you belong to a known group like Al Qaeda (AQ) or Islamic State (ISIS) or Al Shabaab. Perhaps you see yourself as part of these organisations or are just ‘inspired’ by them.

Imagine also that you have been planning for the ‘big one’ for some time now. This plan will end in a spectacular attack that will capture the attention of the world. You may die in the process but you will be famous (or should that be ‘infamous’?).

Why go to that length? After all, any terrorist can carry out a small-scale act with nothing more than a knife or a car or even a golf club (as ISIS wannabe Rehab Dughmosh did in Toronto in 2017). As these are much easier deeds to plan and execute why risk something more complicated and more time-consuming? Such an operation opens you up to detection, infiltration (with a human source or surveillance or intercepted communications), and interdiction. Why not settle for less?

The answer is an easy one. Not only will your success get you on the front page of every news source in the world and every Web page but it will strike a chord as well as fear in the hearts of all (or at least you hope it will). There is nothing like seeing an iconic building or statue falling to the ground to tug at our emotions: this is why every dystopian sci-fi movie shows the Statue of Liberty in New York keeling over. If the symbol falls because of the actions of terrorists it is even more memorable.

What is the evidence for this desire by terrorists to hit symbolic targets? Here are a few examples:

- Algerian GIA terrorists planned to explode a hijacked plane over the Eiffel Tower in Paris in 1994; in 2014 a French jihadist was plotting to bomb both the Louvre and the Eiffel Tower;

- The 9/11 hijackers chose to fly the aircraft they had commandeered into the World Trade Center towers in New York and the Pentagon in Washington (the fourth airliner which crashed in Pennsylvania may have been headed for the White House);

- Canadian jihadi Michael Zehaf-Bibeau tried to breach the Centre Block of Parliament Hill after killing a soldier at the National War Memorial in October 2014;

- Paris’ Stade de France, that country’s national sports stadium, was one of the targets of the 2015 jihadist cell which killed 137 people;

- The 2002 Bali bombings by Jemaah Islamiyah targeted largely Australian citizens in one of Indonesia’s most important tourist sectors.

One would think that the security in place around such highly symbolic venues would deter terrorists and lead them to aim for ‘softer’ targets. The sheer importance and high visibility of these spots may override any doubts about success. In addition, security protocols may not be as effective as assumed. The 6 January 2021 riot at the US Capitol (which I am NOT calling a terrorist incident) demonstrated that even the American Senate was open to a breach by a semi-organised mob. Zehaf-Bibeau’s 2014 attack on the Canadian Parliament showed that a lone actor could get that close to elected leaders (the Prime Minister was in a caucus meeting metres away from Bibeau when he was killed by Parliamentary security).

To these events we have to add assassinations by terrorists. A few examples will suffice:

- In 1984 Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was killed by two of her Sikh bodyguards in the aftermath of the decision by her government to storm the Golden Temple in Amritsar, the holiest shrine for Sikhs;

- In May 1991 Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) claimed the assassination of Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi;

- In the late 19th and early 20th centuries anarchist terrorists killed several world leaders including Russia’s Tsar Alexander II (1881), Spanish Prime Minister Antonio Canovas de Castillo (1897), Italy’s King Umberto (1900) and US President McKinley (1901).

Assassinations are, by definition, acts of political violence against high level public figures and, hence, highly symbolic.

In short, while we will continue to see low level terrorist attacks against targets of opportunity by a variety of groups with a range of motivations – the so-called ‘Nike’ brand of terrorism (‘Just Do It’) – there will also be the periodic symbolic act. It is as if terrorists too want their ’15 minutes of fame’.

Written by Phil Gurski, CEO of Borealis Threat and Risk Consulting Ltd.