How terrorists get their victims where they want them

Terrorists look for the big spectacular, they know the effects of a massive attack. This usually means loss of life and the destruction of buildings and infrastructure. Generally, their aim is to cow the general population or goad a government into action in ways they deem beneficial to their cause. Journalist Lawrence Wright was one of the first to suggest that bin Laden's goal all along was to lure the United States into Afghanistan, which had long been called 'The Graveyard of Empires’.

If you visit the MI5 website, they itemise the many different methods of attack; many of which are wearyingly familiar. But the security service also talks about the terrorist’s ability to innovate and goes on to cite the Paris attacks which involved a complex plot deploying ‘multiple attackers and a range of weapons’.

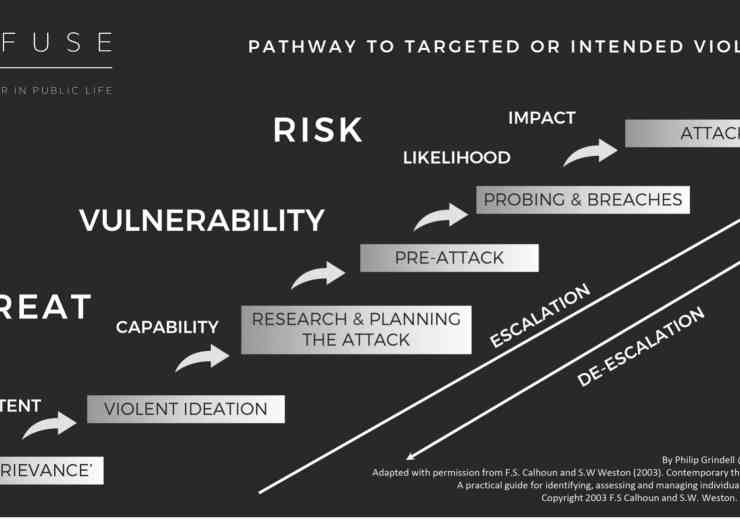

Terrorists are agile and are constantly searching for new ways to manipulate their victims to get them where they want them to inflict the greatest amount of harm.

US embassy attack

In 1998 terrorists attacked United States embassy buildings in two East African cities. More than 200 people were killed when truck bombs exploded in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. At the time I was working for ABC News and was despatched by their London bureau to go to Kenya to help cover the story.

Twelve Americans died in the attacks, but the vast majority of casualties were African citizens. The explosion in Nairobi damaged the US embassy but far greater devastation was done to the nearby Ufundi Building. Thousands were injured in the attack and while covering the story we visited local hospitals where they were taken. Many of the victims had terrible facial wounds and were blinded. We soon found out why.

When the terrorists drove their bomb laden truck to the embassy, they opened fire on the security guard at the gate to gain entry. They also threw a stun grenade at other guards and this small explosion was heard by those in surrounding buildings, bringing many people to the windows. Moments later the truck bomb detonated and windows within a half mile radius were shattered causing terrible injuries to people’s faces. Whether this was the assassin’s intention it’s impossible to know but the small blast followed by the huge explosion had terrible consequences.

For the moment at least, and I may be tempting fate here, the spectaculars seem to be in obeyance. Perhaps this can be linked to Covid and the subsequent lockdowns which has led to atomised working. Terrorists like their victims in tightly packed groups.

Credit should also go to the security services who are now far better at uncovering large, sophisticated plots. However, once again, terror groups have innovated and now often rely on individuals to carry out their atrocities.

Lone actors

In London we endured the 2005 attacks on the tube and bus networks when 52 people were killed and hundreds more were injured in explosions on three Underground trains and a bus. It happened the day after London was awarded the 2012 Olympic Games. Since them we’ve seen a string of terror attacks in the capital largely perpetrated by lone actors.

In March 2017 five people were killed and many more injured by a man targeting pedestrians as he drove across Westminster Bridge. Aside from jumping into the Thames, there was no avenue of escape. He went on to crash into the gates of Parliament before fatally stabbing PC Keith Palmer.

In June of the same year three terrorists drove a van at people walking over London Bridge before staging an attack in nearby Borough Market. Eight people were killed including the attackers who were shot dead by police.

Unrepentant fanatic

The most recent, most egregious example, of a fanatic manipulating the system to put his intended victims in extreme jeopardy was another attack on London Bridge perpetrated by convicted terrorist Usman Khan.

In 2012, Khan pleaded guilty to preparing an act of terror and was sentenced to a 16-year prison term. He was released halfway through his sentence and had been living in Stafford following his release on licence in December 2018.

While in prison Khan is reported to have written a letter asking to take part in a de-radicalisation course. In the letter, obtained by ITV News, Khan wrote: “I would like to do such a course so I can prove to the authorities, my family and soicity [sic] in general that I don't carry the views I had before my arrest and also I can prove that at the time I was immature, and now I am much more mature and want to live my life as a good Muslim and also a good citizen of Britain.” Unfortunately, he was taken at his word.

In November he travelled, unescorted, by train, to attend a prisoner rehabilitation initiative run by Cambridge University at Fishmongers Hall on London Bridge.

He gamed the system which allowed him to go on a deadly rampage among an entirely unprotected group of people who were all gathered to help benefit his life and others like him. He repaid that trust by taping knives to his wrists and killing two young people: Saskia Jones and Jack Merritt.

Members of the public subdued Khan with a fire extinguisher and an ornamental Narwal tusk before police, fearing he was about to detonate a suicide vest, shot him dead. The vest was a fake.

To combat these opportunist attacks the security services, and the public must be on their guard to respond to new attack vectors. Anyone walking over the bridges of central London will see that barriers are now in place stop attackers driving at pedestrians.

Similarly, we are constantly being reminded of the See it, Say it, Sorted mantra which is designed to keep the public on their guard. Authorities often struggle to tread that fine line between keeping the public safe and aware without unnecessarily alarming them.

Tech innovation

From a terrorist’s point of view these attacks have often proved successful perhaps because of their low-tech nature. Security services inevitably find it difficult to track individuals acting alone brandishing knives or driving cars. Where terrorists are anything but low-tech is when it comes to their use of social media.

An article on the Lawfare website points out that at its peak, ‘Islamic State operated more than 46,000 Twitter accounts and could push content to millions of people’. Largely, because of their ability to manipulate social media, they were able to draw more than 40,000 foreign fighters from 120 different countries to their theatre of operations in Iraq and Syria.

The group also used social media to plan and coordinate terror attacks. Discussions could become virtual and removed the need for face-to-face meetings between those planning an attack and the operative who was to carry it out.

Their approach coincided with a huge rise in the numbers of people using social media. In 2010 Facebook had roughly 600 million monthly users. By 2014 that number stood at 1.4 billion. What was once niche had become mainstream.

WhatsApp and other similar applications offering end-to-end encryption played into their hands and allowed inaccessible communications between jihadists.

On 24 July 2016 Mohammed Daleel detonated a suicide bomb at a German music festival. The plot was kept from the authorities and the bomber was the only fatality though fifteen others were injured.

The Lawfare website quotes a discussion between the bomber and his handler that took place over social media just prior to the attack. It’s quite clear that Daleel was very fearful, and the attack might not have happened at all had the handler not been online.

Daleel: [The music festival] will be over soon, and there are checks at the entrance.

Handler: Look for a suitable place and try to disappear into the crowd. Break through police cordons, run, and do it.

Daleel: Pray for me. You do not know what is happening with me right now.

Handler: Forget the festival and go over to the restaurant. Hey man, what is going on with you? Even if just two people were killed, I would do it. Trust in God and walk straight up to the restaurant.

Social media companies have faced pressure to remove jihadi and other extremist material but as this chilling dialogue indicates apps can have many uses.

So how are we best placed to avoid putting ourselves in danger? How can we escape being put where terrorists want us?

Vulnerable muster points

Just before the pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns forced us to work from home, I was at a meeting at the offices of a client in one of the newer skyscrapers in the City of London. The fire alarms sounded and although it was clearly a drill, all those inside had to quit the building and assemble at a muster point nearby.

The building boasts more than thirty floors, so it took more than an hour to clear the site as we weren’t allowed to use the lifts and had to walk down the emergency staircases. Everyone was told that the muster point was Leadenhall Market, which is where we all went to be accounted for.

Perhaps it’s my over fertile imagination but I’m sure I wasn’t the only one thinking what a vulnerable group we all were standing in large groups waiting to have our names checked. Nothing happened but as offices start to be repopulated and work moves away from home perhaps it’s this kind of drill that needs looking at. Was it a good and effective exercise or could it have played directly into the hands of terrorists?

Terrorists are agile, innovative, and as has been said many times have only to be lucky once whereas security services are charged with keeping the public safe at all times. We may have been lulled into a false sense of security during the pandemic with its concurrent drop in terror activity. Unfortunately, we can be quietly confident the threat has not gone away.

Written by Jim Preen, YUDU Sentinel Crisis Management director.

Jim designs and delivers crisis simulation exercises and is responsible for the company’s written material. Formerly a journalist, he worked at ABC News (US) where he covered the Gulf War and the Bosnian conflict. He won two Emmys while working at ABC.