Tackling terrorism in the drone zone

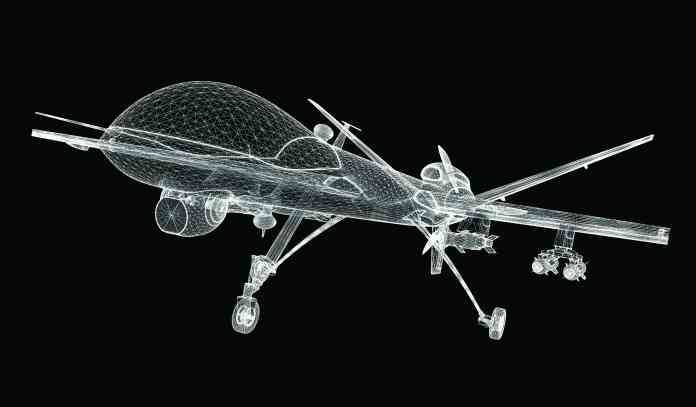

The development in drone technology has soared over the last few years. With the potential for criminals and terrorists to exploit the technology advances, Counter Terror Business analyses the potential use and misuse of unmanned aerial vehicles In December 2016, American electronic commerce company Amazon released a video explaining the development of drone technology to ‘safely deliver packages to customers in 30 minutes or less’. Amazon Prime Air, as it is named, has been trialled in Cambridge and has the potential to transform and enhance the services that the company offer, providing quicker delivery of goods and increasing the safety an efficiency of the transportation system. With a capability to deliver packages weighing up to five pounds in 30 minutes, Amazon argue that the unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) will be ’as normal as seeing mail trucks on the road’. More importantly for this discussion, the delivery giant states that safety is the top priority, with all vehicles including ‘sense and avoid’ technology. Countering Drones, a conference organised by Defence IQ, released an infographic in the build up to its December 2016 event, stating that ‘amongst the optimism [for drone technology] is a creeping concern about the security and safety threat that this technology presents to critical national infrastructure, homeland security and a range of commercial sectors’. While companies such as Amazon can enhance their offering and capitalise on their efficiency by developing the UAV commercial market, it is important that such innovations are effectively measured against the risk posed by drones. Eyes in the skies or clouded vision? The use of drones within the defence and security sectors, as well as in military use, has developed at the same pace as the commercial innovations explored at companies such as Amazon. Created for use in situations where manned flight is considered too unsafe or high risk, UAVs offer military units the ability to have constant surveillance on the activities and movements of both their own troops and those opposing them. A 24/7 ‘eye in the sky’ allows surveillance staff to receive real-time imagery and intelligence of activities on the ground, without putting lives at risk, at least not immediately at risk. UAVs, as their name suggests, are unmanned, but are piloted, with a trained crew at base steering the craft, analysing the images which the cameras send back and acting upon the information that they receive. They are easy to operate and provide distance and anonymity to their operators, with battery improvements and higher technology cameras providing uninterrupted access to the air. However, the use of drones for surveillance purposes has been exceeded by use for air strikes. Although much remains unknown, it has been reported that there were ten times more air strikes (563) in the covert war on terror during President Barack Obama’s presidency than under the Presidency of George W. Bush (57), mainly on suspected militants in Pakistan's tribal areas. Whilst the Obama administration continues to say that drone strikes are ‘exceptionally surgical and precise’, the figures suggest otherwise. According to reports logged by the Bureau,/i>, between 384 and 807 civilians were killed in Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen as a result of the drone strikes. The argument for use is that it prevents the need to send in military personnel for costly ground wars, but human rights groups have a lot of support in contesting the continued use of drones in military activity. Drones for terrorism Additionally, it was reported in January that Islamic State are using drones to drop explosives on civilians and troops advancing in districts of Mosul, with markets in the eastern part of the city, where civilians gather in large numbers to stock up on food, targeted. More than one million civilians remain inside Mosul, despite ongoing campaigns to drive Islamic State from the city. Causing further concern, a research paper has suggested that Islamic State are planning to ‘marry together two technologies, drones as a dispersal device and chemical, biological or radiological material as the dispersant’. Professor David Hastings Dunn, of the University of Birmingham, has penned his concerns on the possible ‘technology transfer’ of techniques and tactics used in Islamic State planning. He argues that drone attacks could be ‘psychologically unnerving and terror inducing’ and that security and military officers should be well aware and prepared for the possible ‘weaponising [of] a drone to carry a chemical agent’. On a separate note, but in defence to the threat of drones, Hastings Dunn refers to the Paris attacks, particularly concerning the suicide bombers who unsuccessfully sought access to the Stade de France. Perimeter security prevented the terrorists from getting inside the stadium, but had they attached their bombs to drones, the damage could have been far more devastating. Briefly returning back to the Countering Drones conference from December 2016, over 75 per cent of attendees believe that there is a strong likelihood of a major drone-related security incident in the near future, with over 35 per cent believing that it is inevitable. A tool for both sides in the race? In Counter Terror Business 24, Gary Clayton, of the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Systems Association, explored whether the security services had the same opportunity to use the advances in unmanned technology and analysis of the data collected as the terrorist. He argued, using several examples, that it is not the technology that is the problem, but the user and intention applied to it that has the potential to create havoc. UAVs have the potential to give the security services a better integrated picture of the playing field through enhancing situational awareness. However they also give the terrorist the ability to act at arm’s length - ’it is not the technology – it is the user that makes the difference’. Moreover, regulation, a hot topic in commercial UAV use in the UK, will never maintain pace with the changing face of technology. The drone market will keep changing, with new models, new capabilities and new uncertainties added every week. Present legislation restricts flight in the urban environment whereas flight in the country environment is far less restricted. Secondly, those planning to use UAVs for terrorist or criminal activity, such as drug smuggling, are unlikely, or perhaps never likely, to feel restricted by regulation. Therefore, countering drones will gain prominence as the preferred method of tackling the terrorist drone threat. The risk of shooting a drone out of the sky is incredibly high, especially if there is a chance that the drone is carrying explosives. Among the companies investing in this industry are the MITRE Corporation, who have launched Counter-Unmanned Aircraft System (C-UAS), a competition for drone defence, seeking inexpensive ‘non-kinetic’ solutions to countering drone threats. Elsewhere, OpenWorks Engineering has created the SkyWall 100 that fires a projectile with a net that envelopes the drone and parachutes it to the ground safely, whilst Radio Hill Technologies' has developed technologies that jam the radio communication between the drone and its operator. The message behind this is that the threat of drones is well known among industry and government, but the potential retains an overwhelming appeal. Like the majority of military technologies, opposing military forces will both seek to gain the upper hand in drone warfare. UAVs for surveillance, whilst useful, are no longer the threat. As Professor David Hastings Dunn points out, the potential within drone use, as concerning as it may be, is fast becoming a reality. It will not be long before the next phase of drone development is established. Let’s hope it is not as the expense of mass fatalities.