Pool Re SOLUTIONS Annual Review 2021 - Special Edition

What has been our response and how do we improve it?

Back in the 80s and 90s, it was very much a long-term game. There were relatively few active members of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), we knew who they were, where they lived, and we had extensive data bases on them and their networks. We undertook intensive surveillance operations, through active and passive means and relied heavily on human sources and technology to provide us with the edge. We took down the hierarchy – difficult with today’s Islamist terrorists which operate on a decentralised approach – disrupted their supply chains and focused on their finances and supporters.

In the 1990s radical Islam, and the growth of Al Qaeda (AQ), was not seen as a problem facing the UK. I think it’s important to make the distinction here between our understanding and response to the threat of radical Islam pre and post 9/11, when the scale of the potential threat became clear. The French intelligence services did warn us of the growing threat and coined the term ‘Londonistan’ because of the presence of a large number of radical Islamists, mostly from Algeria and some who had served in Bosnia, who were living in London. But these individuals did not pose a direct threat to the UK where PIRA was still considered the primary terrorist threat. But even in 2001, the threat of Islamic terrorism against the UK was still seen as low, and it remained so until the first successful attack in 2005 (although there had been a ricin plot interdicted in Wood Green, with the Islamist perpetrators intending to attack the London Underground in 2003).

CT operations became more challenging and more global in the late 90s and early 2000s, as opposed to localised campaigns, primarily because of the safe havens in Afghanistan and Iraq (although international terrorism, vide Palestinian terrorism, had always been global.) There were a large number of suspects, with only a small handful known to the authorities. We lacked the necessary ‘human sources’, and AQ was more alert to our surveillance techniques and methodologies. They went ‘off-grid’ and were able to plan catastrophic attacks, in the late 90s, such as the USS Cole, the US embassy in Dar Es Salaam and, of course, 9/11.

In 1993, MI5 had only 2000 staff and 70 per cent of its efforts were focussed on terrorism, much of it targeted towards the activities of the IRA and domestic terrorism. 25 per cent was devoted to counter-espionage and counter-proliferation - the latter against the growing threat from ‘weapons of mass destruction . . . nuclear, chemical and biological.”

MI6 was still coming out of the shadows of fighting the Cold War and, despite having more overseas stations than it does today, Islamist terrorism was not seen as a threat. The CT agencies – MI5, MI6, GCHQ, DIS and Special Forces (SF) - were also very stove-piped and we did not share intelligence and knowledge about the threat. MI5 now has 4000+ staff and is funded as part of the Single Intelligence Account (£3.02 billion in 2017–2018 financial year, which includes the budget for GCHQ).

There is a now national network of MI5 agents, with a significant proportion focussed on Islamist terrorism, based out of the Counter Terrorism Units (CTUs), but still with a reasonable proportion leading the efforts against Northern Ireland related terrorism. More significantly, our domestic and international CT policy and operations are combined, taking into account the global, physical and virtual nature of the threat.

9/11 was a huge wake up call for our CT agencies, and the start of a more coordinated international collaboration across the 5 Eyes community (UK, US, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada). Although the challenge of sharing timely and accurate intelligence still existed, and our US partners were in the early years, in my opinion, determined to win the War on Terror on their own terms and often under their own steam. The major challenge in the aftermath of 9/11 was that the so called ‘war on terror’, which was the political cover for regime change in Iraq, became conflated and confused with a ‘neocon’ political agenda. Notwithstanding, collaboration across the UK CT communities improved, albeit slowly. This was enhanced with the implementation of CONTEST, and the four pillars of Prevent, Pursue, Protect and Prepare. This was the first CT policy of its kind, and it endures, with little change, today.

The game changer, in my view, was the creation of the CTUs and (then a network of CT Intelligence Units - CTIUs) in London, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds that fused Police, MI5, MI6, GCHQ and SF Liaison Officers) under the direction of Assistant Commissioner Special Operations (ACSO) and the oversight of Association of Chief Police Offices Terrorism and Allied Matters (ACPO TAM) with a new Home Office department, the Office of Security and Counter Terrorism (OSCT, now named the Homeland Security Group), to provide the policy lead. The attacks in London in July 2005, ‘7/7’ and ‘7/21’, created another strategic shock. This saw the coming of age of the Joint Terrorism Analysis Centre (JTAC), formed in 2003, which brought all the CT agencies together, fusing all source intelligence and full inter-agency cooperation. JTAC is an exemplar organisation, envied by our European partners and has done much to keep the threat of terrorism to the level it is.

Current Threat Landscape

Since 9/11 we have witnessed a huge amount of chaos and uncertainty and the current terrorist threat landscape continues to evolve, remaining complex and confusing, recently highlighted by still unexplained motivations of the perpetrator who, based on what we know, tried to attack the Liverpool Women’s Hospital. The threat from all terrorist constituencies is arguably more dangerous and diverse than in 2000. This concern was recently highlighted by Richard Moore, the new head of the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), who stated that countering international terrorism is now one of the ‘Big Four’ priorities for MI6.

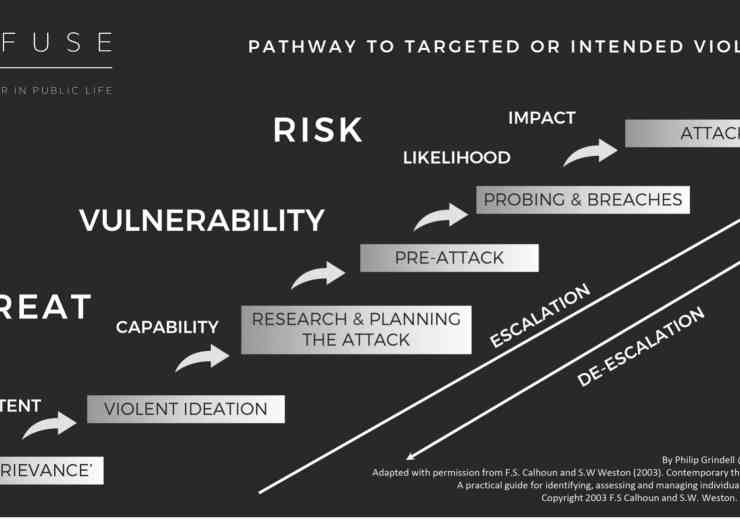

The emergence of the ‘self-initiated terrorist’, i.e. one who acts relatively alone and is informed and radicalised via the internet, appears to be the main threat to the UK. This has changed over the last five to six years when terrorist attacks were a combination of those directed from abroad, frustrated ‘travellers’ who could not get out to the so-called Caliphate and those who simply acted on their own.

The continuing rise of Right Wing extremism is increasingly of concern. This trend is well recognised but during 2021 it certainly saw no sign of slowing, especially in Europe and North America – as illustrated by the riots in Washington in January 2021. Previously confined to the US and Europe it now poses a more transnational and global threat. Right Wing extremism used to be characterised, by some, as ‘hapless and hopeless’. Now a more cellular structure, often portrayed as a political movement with a clear vision and mission, Right Wing extremists have more connectivity and coordination than they did 5 years ago, and, as with Islamist extremism, they have shifted ‘online’ with access to the same suite of highly effective ‘virtual’ tools and resources at their disposal.

However, the chaotic threat landscape does not necessarily mean we are likely to face more frequent or sophisticated attacks, it may simply lead to a broader range of attacks. Experience tells us that terrorists are persistent, and they will continue to plan for mass casualty attacks using the full spectrum of technologies and methodologies available – be they sophisticated devices or those which are more readily to hand and off the shelf.

I would argue that we need to deal with terrorism end to end, looking at both the drivers of terrorism as well as its consequences. The involvement of businesses and the private sector is crucial to our success. As Neil Basu, senior lead for CT in the UK, commented at a Pool Re conference in 2019, ‘there can be no prosperity without security and that every business needed to be a counter terrorism business’. The forthcoming Protect Duty legislation will put more requirements on businesses, especially those operating in publicly accessible locations to protect their customers and the public from terrorist attacks.