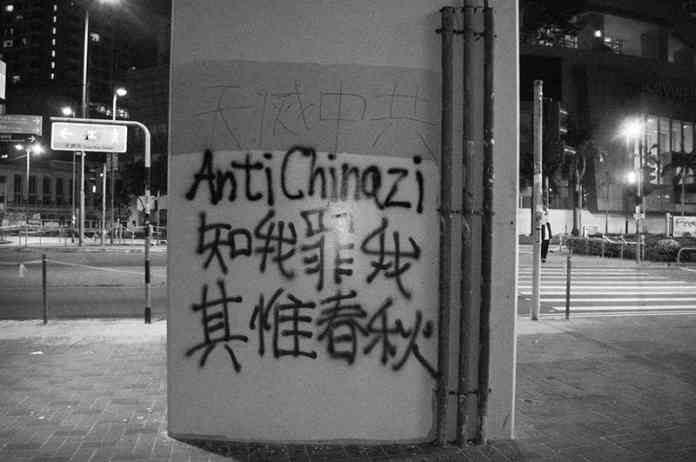

Hong Kong and China: A perspective

Amy Pope explains the cyber security, geopolitical, and global business impact of UK opposition to China’s moves in Hong Kong, and what companies can do about it

The recent national security law imposed by China on Hong Kong has fuelled the ongoing concerns around human rights abuses within the region, as well as raising serious concerns around data privacy, business continuity, and autonomy across the global community.

Indeed, following promises of amnesty for Hongkongers fleeing the conflict by the British Government, China warned the UK would ‘bear all consequences’ should it grant residency to those seeking to escape Hong Kong.

The backlash from the conflict is far-reaching, with tensions spilling over into the business world, as the security law continues to put pressure on Hong Kong-based organisations to publicly back the law’s sanctions.

The security law’s impact on business

From a national security point of view and from a business security perspective, the law should give businesses and governments some serious pause. It cements concerns that China has little intent in respecting traditional expectations around the safeguarding of information or protecting of intellectual property.

That’s not to say that every single Chinese business is on a one-stop mission to sweep up all information from their users and put them in a compromised position. Chinese businesses represent a significant lynchpin upon which much of the world’s economy is growing.

The real issue is the point at which the Chinese Government decides to interject and demand or appropriate user information without meaningful fear of repercussion. It is increasingly apparent that Chinese businesses have very little leverage to push back on these demands.

It is for this reason that so much conjecture exists around Chinese-owned brands like TikTok and Huawei. The polemic isn’t centered on the services these brands offer, or even necessarily their corporate governance. The fear arises from the Chinese Government possessing the ability to use them as a conduit for accessing information that would, ordinarily, be secure and private.

Underpinning this concern is the broad arrest authority under the new law with little regard for due process, as well as provisions allowing suspects to be sent to the Chinese mainland for trial. The vague wording of the law raises serious concerns about its potential impact on the business world, leaving little recourse to individuals caught in its crosshairs.

Time to take a stance: How should businesses safeguard?

For businesses operating in Hong Kong, an immediate first step is to cordon off their Hong Kong branch and establish some blue water between their Hong Kong based businesses and their global houses. Businesses must assure their clients, investors, and governments that their affiliation with Hong Kong based entities does not fundamentally compromise their users’ data or other sensitive information. Some businesses are taking a step further and relocating their employees to nearby countries outside of Chinese jurisdiction.

More fundamentally, businesses must weigh the short-term monetary ramifications of maintaining their business in Hong Kong with the long-term impacts of a policy that allows the government to put a heavy hand on business practices. The issues will not go away. It is more likely that the ability to conduct business in a country that lacks transparency, due process of law, and sufficient respect for privacy and safeguarding of intellectual property will become untenable. While businesses will be reluctant to get involved in Chinese politics, it is nonetheless important to communicate that these privacy and security risks can negatively impact foreign investment and investor confidence.

For businesses outside Hong Kong and China, the most pressing concern is the Chinese Government – or affiliated state actors – backdooring access into their infrastructure – a threat made more real in the face of the British government’s response to Huawei, the Hong Kong protests, and Covid.

In my experience in both government and the private sector, Chinese state affiliated actors may sit inside an organisation’s server, undetected, scraping information without opposition.

Businesses need to be alive to the fact that they are likely targets, especially if they operate within a sector that represents particular interest to the Chinese Government, such as travel or banking.

Increased collaboration between the public and private sector

Aside from the obvious basics (regular cyber health hygiene checks, employee training on phishing attacks, routine software updates), one of the strongest defence mechanisms against cyber attacks is improving the connectivity between the private and public sector.

I was working on the National Security Council at the White House at the time of the Sony Pictures hack of 2014. That breach (which was not attributed to a Chinese state affiliate) yielded 100 terabytes of sensitive data as well as proved reputationally damaging to the company, forcing us to reconsider and improve information sharing between the private sector and US Federal Government entities. Ultimately, as a result of that and other hacks, we wrote new policies on how the US Government should work with the private sector to proactively share information about cyber targets. We recognised that the only way to counter the threat was to do so hand-in-hand with the private sector.

The United States has certainly not mastered the art of information sharing, but unfortunately, there are precious few examples of governments finding ways to proactively share this information with the private sector targets of the attacks. For countries – and businesses -- to have the best chance of fending off such attacks, there must be much better flow of information between the two entities. It’s mutually beneficial -- the government learns about the most common intrusions targeting the private sector, and businesses are privy to vital information about the tactics and methods being used within their industry.

This approach means fundamentally changing the ‘name, shame, and blame’ culture that’s rampant in the business world when it comes to cyberattacks. In the UK, the ICO plays an incredibly important role in ensuring businesses are taking seriously their responsibility to protect data. If a breach occurs, the ICO can come down hard, with serious fines and business-crippling consequences.

Absolutely, there must be consequences – especially if a company has failed to take basic cyber security precautions. But the government should not shift the responsibility entirely onto the shoulders of business – especially when these attacks are instigated by sophisticated foreign state actors. Instead, we must encourage higher levels of collaboration between the regulators, the private sector, and government bodies.

By joining forces, rather than resorting to harsh punitive measures, we can learn from each other and prevent similar breaches from taking place in the future. That’s the balance that needs to be struck.

About the author

Formerly US deputy homeland security advisor to the president of the United States, Amy Pope has managed a range of high-profile, diverse challenges at the highest levels of US government from countering violent extremism to promoting refugee resettlement to leading its comprehensive effort to combat Zika, Ebola, and other public health threats.

As a partner at Schillings, she now advises corporate and individual clients on responding to and mitigating crisis. Prior to joining the White House, Amy worked in several positions at the US Department of Justice and served as counsel in the US Senate.

digital issue