Building a critical network of support for first responders

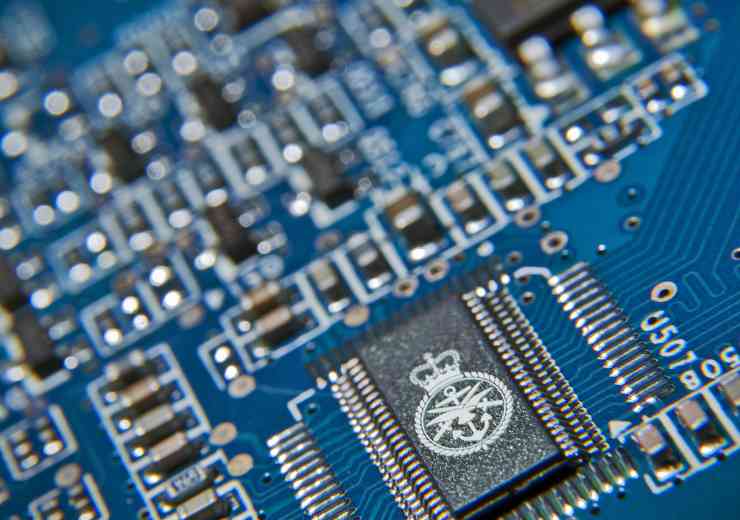

Smart devices need smart analytics

The number of devices and the amount of data identified and collected by the IoLST are anticipated to grow exponentially in the next several years, so it is important to be able to efficiently evaluate the data as it only becomes useful information once analysed. Take facial recognition as an example: the analytics need to be smart enough to identify the same face taking the same route several times and flag it as suspicious. For surveillance, the analytics need to be sophisticated enough to recognise the lone package in an airport that hasn’t been moved within critical timescales, and send an alert to the authorities.

Many consumer devices can also assist first responders, and have huge potential via the IoLST. Connected medical devices can provide key information to help monitor chronic conditions such as diabetes and asthma, and enable remote intervention so patients do not always have to travel to the hospital for routine checks. This is not only more convenient for the patient, but frees up the time of health professionals to increase their availability for critical care.

Smart watches and fitness trackers have been widely adopted by consumers, and can send emergency messages if they detect a dangerous health issue, alerting health professionals to a potential heart attack victim, for instance, and sending the exact location of the casualty. There are also ‘connected pills’ that send a message to health carers once digested by the patient; and smart medicine dispensers that record and transmit usage. Both of these can enable a higher success rate for prescribed treatments, especially for the elderly, and health professional need only intervene when necessary rather than having to constantly check up on the patients.

Virtual assistants such as Amazon’s Alexa, as well as home monitoring and security systems, also have the ability to receive feedback from sensors to alert homeowners and public safety professionals in the event of a suspected burglary, or a sudden rise in temperature indicating a fire. These connected devices can also provide status reports, including real time video. In the future it is likely that photos, video and situational data sent to emergency services via 112, 911 or 999 will be rapidly analysed and converted into actionable information, so home assistants currently used for personal convenience will become IoLST assets for first responders.

Connected devices for critical support

For fire and rescue services, the use of connected unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) – or drones – to scope out the extent of a wildfire, or to give an accurate overview of a road or rail crash, is becoming more common. Thermal imaging can pinpoint the heart of a fire, with video and images sent to the incident command and control. Land-based robot drones that can ‘see’ through smoke are sent into burning buildings to transmit images of the status, or into situations where hazardous materials are involved so firefighters can assess the best way to respond to the incident. This not only keeps the firefighters safer, it can improve the outcome of the response.

Police forces are increasingly adopting body cameras that can record unfolding events for post-situation analysis and evidence, and the newer versions can live stream video from an incident over broadband networks. This live streaming video capability is a critical tool for police on the front line, sending crucial information to command and control to enable the most informed response to an incident and improve officer safety. It is important to note, however, that each country will have its own rules and regulations around data privacy and civil liberties, so implementing devices such as body cameras and drones is not a simple or automatic process.

It is clear that public safety and commercial users are recognising that there are many new tools that can be utilised to support the work of first responders, and provide insights to manufacturers, service providers, public safety and government regulators to ensure these technologies are developed and deployed in a way that best serves and supports our first responders.

Case study – Drones as First Responders

In December 2015 the Chula Vista Police Department in California formed the Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) Committee to study the use of the technology in its public safety operations. UAS Committee members met dozens of times to study best practices, policies, and procedures regarding the use of UAS technology in law enforcement. A special focus of the team’s research was an effort to address concerns about public trust, civil liberties, and the public’s right to privacy during the operation of CVPD UAS systems.

Prior to implementing its UAS Program, CVPD discussed its plan for UAS operations in the media, in public forums, and in posted information about the project on the CVPD website. This outreach included a mechanism for the public to contact or email the UAS Team to comment on CVPD’s UAS policy, or to express concerns or provide feedback. It is important to note that, out of respect for civil liberties and personal privacy, CVPD’s UAS Policy specifically prohibits the use of UAS Systems for general surveillance or general patrol operations. After exhaustive planning and research, CVPD activated its UAS Program in the summer of 2017 to support tactical operations by CVPD first responders.

Since October 2018 and with strong support from the community, Chula Vista Police has been deploying drones from the rooftop of the Police Department Headquarters to 911 calls and other reports of emergency incidents such as crimes in progress, fires, traffic accidents, and reports of dangerous subjects. This Drones as a First Responder (DFR) System is transformational by providing first responders with something they have never had before, a faster perspective of the situation since the drones are deployed to the incident and arrive well before ground units.

The on-board camera streams HD video back to the department’s real-time crime centre where a teleoperator, who is a trained critical incident manager, not only controls the drone remotely, but communicates with the units in the field giving them information and tactical intelligence about what they are responding to. The system also streams the video feed to the cell phones of the first responders and supervisors on the ground so they can see exactly what the drone is seeing.