The application of UAVs in managing port security

Results and discussion

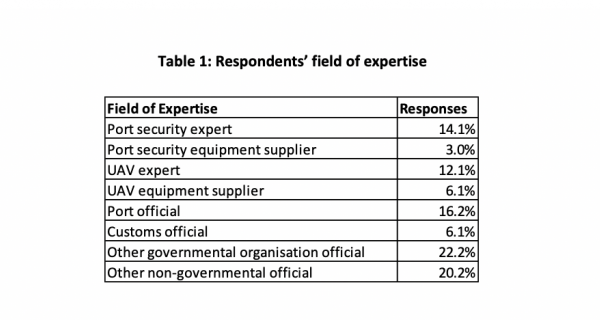

A total of 66 respondents participated in the survey for our study. The data were collected from Kuwaiti port security staff using online tools, while taking into account relevant ethical considerations. The first question was about the field of expertise of the respondents and the results are summarised in Table 1.

As Table 1 shows, the majority of the respondents were governmental organisation officials. Only 12 per cent of the respondents were UAV experts, while six per cent were suppliers of UAV equipment. 14 per cent of the respondents were port security experts, which increases the reliability of the data they provided. The next question referred to the respondents’ familiarity with UAVs, with the results shown in Table 2.

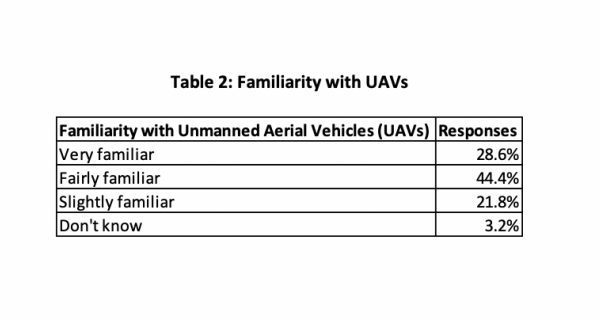

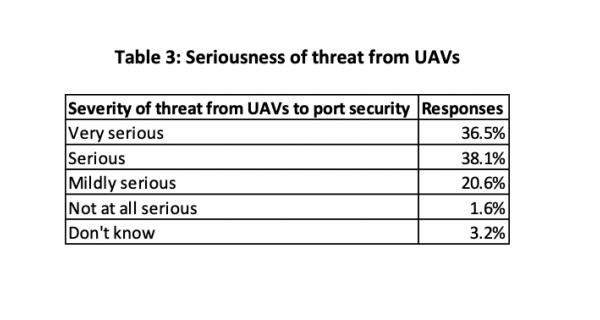

As the results show, only 28.6 per cent of respondents indicated that they were very familiar with the devices in question, although a further 44 per cent of respondents declared that there were fairly familiar with the device. Under a quarter (22 per cent) said they were slightly familiar with UAVs, while only two respondents (three per cent) claimed they knew nothing about UAVs. The third question of the survey was ‘how serious do you consider the threat from UAVs to port security?’ As shown in Table 3, 74.6 per cent of the respondents considered that the threat UAVs posed to port security was either serious (38 per cent) or very serious (36.5 per cent).

As observed in the literature before 9/11, the most significant threats to port security were drug smuggling and organised crime. However, after those attacks, terrorism became a significant threat. One of the most significant current threats to port security comes from cyber attacks, which could be conducted by terrorist groups using UAVs.

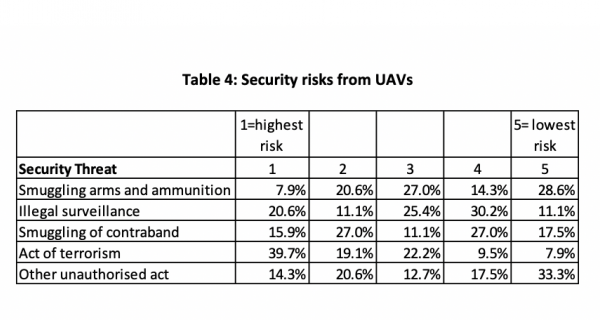

The fourth question was ‘please rank accordingly the risk of UAVs in terms of a security threat where 1=highest risk and 5=lowest risk’. The results are shown in Table 4. The majority of the respondents indicated that the highest risk is that of an act of terrorism: 40 per cent of the respondents indicated the highest risk. Furthermore, 20.6 per cent of the respondents also indicated that there was a higher risk of illegal surveillance using UAVs.

It is also important to observe from Table 4 that the respondents considered that there was a limited risk to using UAVs to smuggle weapons into the secure areas of the port, considering the fact that the UAVs would be able to transport a small explosive device (approximately 1kg) into secure locations.

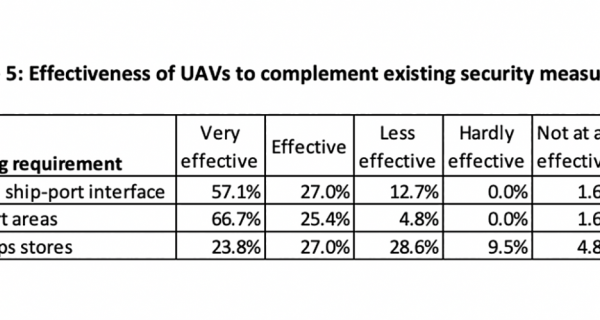

The fifth question was ‘In your opinion how effective could the deployment of UAVs in a port facility complement existing security measures?’ The deployment refers directly to the monitoring requirements as prescribed in the ISPS Code, namely the monitoring of the ship-port interface; port areas; and ships stores (see Table 5).

Despite the security risks that the respondents identified in relation to the use of UAVs by others, Table 5 demonstrates their confidence that UAVs can also be used legitimately to increase port security. Sixty-six per cent of the respondents believed that UAVs could be effective in monitoring port areas that do not benefit from standard surveillance methods. Furthermore, 57 per cent of the respondents also considered that UAVs could be very effective in monitoring ship-to-port interfaces.

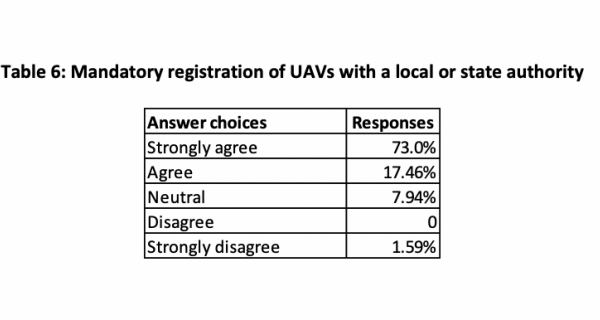

The sixth question was ‘In your opinion should it be mandatory for UAV ownership to be registered with local or state authority?’ (see Table 6).

As we can see from Table 6, nearly three-quarters of respondents (73 per cent) strongly agreed with the registration of ownership with the local or state authorities. This reflects that the number of civilian users of UAV devices is increasing and the authorities have no possibility of determining the purpose for which the UAVs are being purchased. This increases the risks associated with the use of UAVs by civilian users. However, the authorities could not breach the right to privacy of a person, only their right to use a device that can potentially be employed with criminal intent. Nevertheless, the registration of such a device would associate the owner with a specific device identified by a unique serial number. This can both increase the likely legitimacy of the device user and make it easier for the authorities to identify the owner of a device who intended to use it to commit a criminal act. Only one respondent expressed a strong disagreement with the registration of UAV ownership.

The study has revealed some interesting findings regarding the application of UAVs in port security with a view to enhancing security and complimenting existing security regimes. It is also noted that the presence of UAVs controlled with criminal intent can be perceived as a threat to port operations, hence the high proportion of respondents looking for UAVs to be registered with a local or state authority. There is scope for the study to be extended to include a wider geographic area and also to address other nodes in the supply chain beyond ports.